Septuagesima is one of the superficially stranger calendar days in the Prayer Book. The name has a mysterious sound for laics like myself. But, as part of a bigger fast season– especially sundry times midst, say, tumult, conspiracy, and plague– it’s “meet, right, and our bounden duty” to consider it’s origin, purpose, and benefit. Septuagesima is an very commendable pre-Lenten discipline for our holy Church, giving prudential occasion to temper & ready oneself for spiritual battle, to wit we might “beat down Satan under our feet” (p. 56 , 1928 BCP).

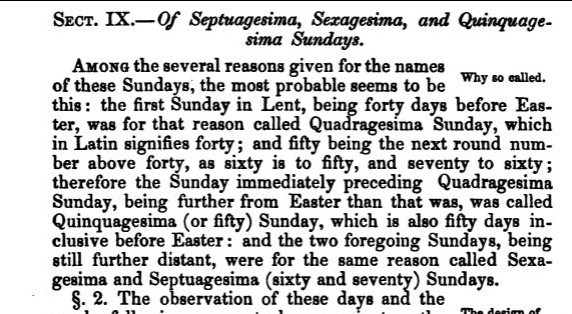

First, let’s supply our definition for ‘Septuagesima’ from Rev. Charles Wheatly’s Rational Illustration of the Book of Common Prayer (1720). We should not be confused by the Latin. “Sept-” simply means “seven-ish”, or ‘seventy’, days before Easter. Hence, Septuagesimatide offers a longer fast season for the improvement of the soul against lusts of the flesh and vanities of the world. The common observation of any pre- or post-Lenten discipline is to make the Church holy by training ourselves against all inordinate and sinful affections. Wheatly’s Rationale explains this peculiar term:

So, the Latin name for the ‘Third Sunday before Lent’ is hardly a shocker. Again, it’s merely ‘seventy-days’ prior to a Resurrected or victorious Christ. The Collect is interesting since it confesses a condition of current judgement & affliction. Whether this be ourselves under mortality, or certain a temporal deprivation or oppression, is left to the reader’s discernment. But the emphasis is about us enduring a justly executed trouble with ultimate confidence in our Savior.

William Nicholl’s Paraphrase (1710) of the same Collect is read here:

While I prefer 18th c. commentators, Massey Shepherd (1952) gives a surprising amount of context regarding this pre-Lenten Sunday’s origin and relation to chastisement. Evidently, it flows from two streams. The first source is Pope Gregory the Great who introduced the Collect upon the invasion of the Lombards in the late sixth-century Rome. So, it has an antique origin with a supplication borne from historical punishment. Shepherd identifies it, along with its two sister collects (Sexa- & Quinqua-), as reflective of “the sad and perilous condition of Italy at that time, not only because of the ravages of the barbarians but also because of the pestilences, famine, and earthquakes that occurred during the period.” (p. 118, Oxford American Prayer Book Commentary). Might we see how such relates to our own precarious and perilous times!?!

Regarding such sundry times, I am reminded of the ‘Homily on the Declension from God’, first part, which explains the instruments of, often bodily, punishment and chastisement:

Another inspiration suggested by Shephered is “possibly some influence upon the Roman Church by the many Easterners then in Italy, who observed an eight-week rather than a six-week Lenten fast.” (p.118). I am highly favorable of anything “old-time” that connects Anglicans to the East (which tends to be a more Semitic church). Besides the sobriety of an extended fast, certainly desirable upon times of danger, the Anglican often times is closer to sister national Churches than the universal Roman. And, it’s largely the Semitic overtones which make the difference, even to the Jerusalem Mother Church of old.

The Gospel reading, Matt xx.1, mentions ‘vineyard’, and Shepherd thinks this might touch the agricultural New Year in the Julian Calendar which the Eastern Churches tend to keep. As part of a pre-Lenten denial of self, we ought (says Wheatly) “to call us back from our Christmas feasting and joy, in order to prepare ourselves for fasting and humiliation, and the approaching time of Lent” (p. 221, Rational Illustration). It may be curious that the Rev. John Wesley in his Sunday Service ‘simplified’ the calendar by adding twelve Sundays in Christmas until reaching the Sundays before Easter, perhaps amplifying the same contrast between Alleluia & merces.

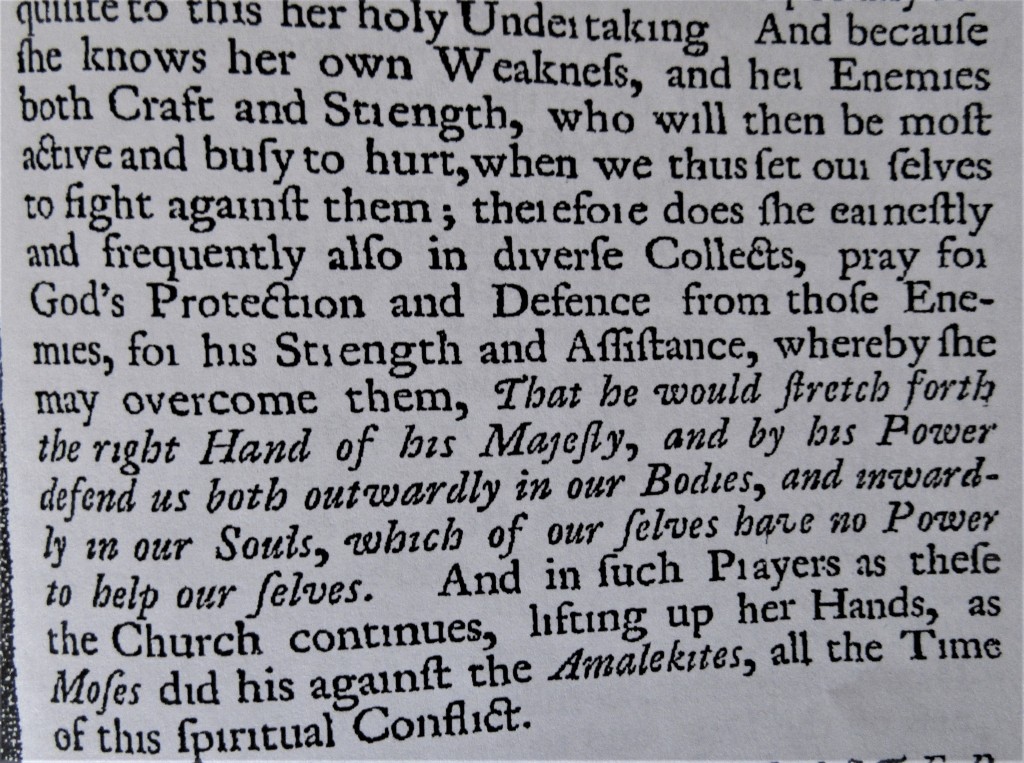

The Epistle, 1Cor ix.24, mentions the rule of the Christian militant, namely, “so run, so ye may obtain” and “fight I, not as one that beateth the air: but keep under my body, and bring it into subjection”. The scripture definitely belongs to the corpus of Christian soldiery, bringing to heel the devil & carnality. Anthony Sparrow underlines this point regarding our battle. Sparrow says, “Though the Church be always militant while she is upon the Earth, yet at this Time (the Time when Kings go out to Battel, 2 Sam xi) she is more than ordinarily militant, going out to fight against her avowed Enemies, the World, the Flesh, and the Devil; making it her special Business to get the Mastery over them” p. 102, A Rationale or Practical Exposition of the Prayer Book). This militancy and call to warfare, by help of ‘Temperance, Fasting, and other Works of Penance and Mortification’, coupled with prayer and the collects of the Church, is compared by Sparrow to Moses’s combat with the Amalekites (e.g., Ex. 17.11):

The Amalekites held the southerly portion of the land of Promise. Interestingly, in the report of the spies to Moses, the combinations of Anakim, Amalekites, Hittites, Jebusites, Amorites, and Canaanites almost describe an encampment of evil, each pitched by a point of the compass. Yet, Israel was commanded to dash their bulwark and eradicate this wicked federation. In other words, to conquer the worldly principalities unto the Kingdom of God. Also, note Sparrows mentions ‘the Power of his Defense’ both for Body and Soul which has parallel in the Morning and Evening ‘Collects for Peace’ as well as in the Litany itself, “that those evils which the craft and subtilty of the devil or man worketh against us, may, by thy good providence, be brought to naught; that we thy servants, being hurt by no persecutions, may evermore give thanks unto thee in thy holy Church; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.” (p. 58, 1928 BCP)

Septuagesima offers a prolonged fast for unusual times and troubles. In this respect, it is much like the Penitential Office of the BCP which can be affixed to the regular Litany upon special occasion or at the discretion of the minister. Septuagesima’s origins seem especially connected to upheaval and plague, so it seems entirely fitting with recent events. It indeed reminds us a great purpose of tribulation– the command to sanctify and make holy the residue of Church. As soldiers we do well to receive training &, thus, be uncompromising about our trampling of sin, even unto perfection. Thus, we are invited to the holy guidance of grace of Christ, so we may be ready to meet our King in clouds and give reckon. A concluding prayer said together by minister and people in the 1928 Penitential Office reads,

Turn thou us, O good Lord, and so shall we be turned. Be favourable, O Lord, Be favourable to thy people, Who turn to thee in weeping, fasting, and praying. For thou art a merciful God, Full of compassion, Long-suffering, and of great pity.

p. 62, 1928 BCP

Leave a comment