Septuagesima is one of the superficially stranger calendar days in the Prayer Book. The name has a mysterious sound for laics like myself. But, as part of a bigger fast season– especially sundry times midst, say, tumult, conspiracy, and plague– it’s “meet, right, and our bounden duty” to consider it’s origin, purpose, and benefit. Septuagesima is an very commendable pre-Lenten discipline for our holy Church, giving prudential occasion to temper & ready oneself for spiritual battle, to wit we might “beat down Satan under our feet” (p. 56 , 1928 BCP).

Continue Reading » This year calamities of biblical proportion has visited these United States, certainly California. For our family, the Prayer Book’s litany has become a regular and important devotion, altering from a liturgy said basically seasonally to one read multiple times a week (1). As troubles unfold, we find certain petitions speaking explicitly regarding our plight, so the last couple weeks the 1928 BCP’s deprecations loomed large. The following hopes to underline their imminence, and discuss this portion of the liturgy’s design. Continue Reading »

This year calamities of biblical proportion has visited these United States, certainly California. For our family, the Prayer Book’s litany has become a regular and important devotion, altering from a liturgy said basically seasonally to one read multiple times a week (1). As troubles unfold, we find certain petitions speaking explicitly regarding our plight, so the last couple weeks the 1928 BCP’s deprecations loomed large. The following hopes to underline their imminence, and discuss this portion of the liturgy’s design. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP | Leave a Comment »

I regret posting this after the passing of John the Baptist Day, but this essay has more to do with it’s octave– or, roughly the time between June 24th to July 1st– close to our Independence Day (July 4th). However, the inspiration for this article really comes from the Canadian BCP which provides a special collect and reading for roughly the same time period, in this case, commemorating John Cabot’s landing. However, we in the United States, or at least on the Pacific Coast, may ritualize a similar event given Drake’s landing ironically falls upon the same famous date of June 24th. Let’s consider how an American, or at least a Pacific Coast, commemoration might be done after a review of Drake’s voyage, and his claim for England in that western part of North America once called ‘New Albion’. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP | Leave a Comment »

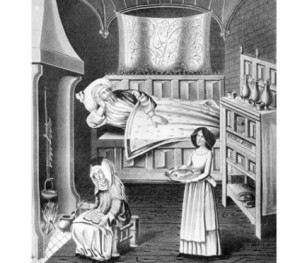

Sweating Fever c. 1551

Usually, I am a bold defender of the 1928 American Book of Common Prayer, namely, because its proximity to historical liturgy as well as relevance to American identity. That said, there are times I find its denuding of God’s occasional wrath lack-luster. Indeed, there are times when individuals, as well as nations, ought to sense due wrath– at least for humility’s sake. Do we believe today’s God incapable of chastisement? Do we take our own sins so light-heartedly they are beyond rebuke? Here, the sanitation the 1662 Prayer against Common Plague in the 1928 BCP is rather disappointing. However, this is not so with the American book(s) in general, and the 1789 (as well as 1892) version kept the best of all concerns. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP | 4 Comments »

The Rev. Thomas Scott. Holy Bible .

Last Sunday our Morning Lessons, as found in the 1943 Lectionary, were Isa. 61.1-3 cf. Luke 4:16-32. Normally, I try to restrain articles about Holy Days of certain Precedent rather than Ordinary Sabbaths. However, this specific lesson stood out because Christ reads to the Jewish Synagogue that portion of Isaiah which declares our Glad Tidings. Of course, ears should perk up whenever scripture sets forth the promises of the Gospel. But, unusual was the Lord’s omission from the scroll of the Prophet his “day of vengeance” (v.2). For me, the Messiah’s manner of reading and preaching left a few questions, especially why dire warning or judgement was absent? As usual, I gleamed what I could from one of my principle 18th-century commentators, mainly the Reverend Scott, late Rector of Aston. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP | Leave a Comment »

Destruction of Ninevah

A couple months ago, our class leader urged me to build a habit of reading scripture daily. So, being a good churchman, I went to straight to the lectionary for my regular course of bible reading. Not surprisingly, I was referencing the 1943 lectionary which is inserted in American 1928 Prayer Books after the same date (see the certificate given after title page). Interestingly enough, for the Eleventh Sunday in Trinity, the Book of Nahum was assigned for the Evening Lesson(s). What shocked me was the wrathful, even imprecatory, language of Nahum’s prose. The selection alarmed me given the usual ridicule of the 1928 American BCP being ‘liberal’. That charge might be better pressed against the 1940 hymnal, yet in continuing Angilcan churches both books are normally found tucked together behind pew benches. But, I’d like to debunk the earlier objection, namely, the American 1928 BCP as a ‘liberal’ book, starting with Nahum’s presence in the lectionary and how penitentialism restored in our devotions by secondary texts, if necessary. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP, Lectionary | Leave a Comment »

Oftentimes the 1928 BCP is identified as part of PECUSA’s downward slide by reason of eroding older penitential language. Some changes were indeed unfortunate but few consider the flexibility of rubrics which may compensate for much of what’s missing. Shouldn’t we be more careful about lumping, say, the 1928 BCP together with its 1979 counterpart? Or, for that matter, doing the same with any of the American BCPs? In time, I’d like to develop a robust defense of the 1928 and older American versions, but in this post I will begin to tackle a common complaint about the 1928, namely, its tendency to displace ‘sin’ out of the prayer book, starting with the Penitential Office.

Continue Reading »Posted in BCP | 1 Comment »

Recently, at Anglican Rose, I sketched a controversy held by Evangelicals in the Episcopal Church against the Oxford Movement prior to the Bp. George Cummins’ departure. According to Cummins, if Evangelicals had been relieved by suggested reforms at the Conventions of 1868/71, many low church-men would have stayed put. The proposed Relief consisted of three points (see link above)– two of which, interestingly, have since been met half-way (say, by changes in canon and/or rubrics). However, the third matter-of-relief had to do with the term ‘regenerate’ in the baptism of children. It’s this latter proposal I’d like to investigate. Continue Reading »

Posted in BCP | 5 Comments »

Dr. Roberta BayerI read this article in the Anglican Way Magazine and reprinting it here with Dr. Bayer’s kind permission…………

The “Deep Churchman” – Commentary on “C. S. Lewis, 20 Years After”

By Roberta Bayer

By Roberta Bayer

C. S. Lewis described himself as a “deep churchman,” in the passages quoted by Roger Beckwith. His avowed intent was to remedy misconceptions about the Christian past; he taught the mere Christianity of historic Christendom, considered in its unity, rather than parsed for disparities. “We are all rightly distressed, and ashamed also, at the divisions of Christendom”, Lewis wrote. But those who have always lived within the Christian fold may be too easily dispirited by them. They are bad, but such people do not know what it looks like from without. Seen from there, what is left intact despite all the divisions, still appears (as it truly is) an immensely formidable unity. I know, for I saw it; and well our enemies know it. That unity any of us can find by going out of his own age.”

What does Lewis mean by ‘going out of one’s own age’? Despite the gaps and discontinuities found within Christian theological and liturgical history, Lewis’ approach illustrates a certain unity within Christianity that is not only visible from the outsider’s broader historical perspective, but also is worthy of our attention in attempting to reconcile contemporary differences between Evangelical and Anglo-Catholic traditions through a “deeper” perspective cultivated by wide reading. Furthermore, Lewis

suggests that contemporary controversies between Evangelical and Anglo-Catholic may share a good deal more in common than they realize. Of historical ecclesiastical divisions, he writes;

“Nothing strikes me more when I read the controversies of past ages than the fact that both sides were usually assuming without question a good deal which we should now absolutely deny. They thought that they were as completely opposed as two sides could be, but in fact they were all the time secretly united— united with each other and against earlier and later ages—by a great mass of common assumptions.”

Lewis suggests that the only safety against blindness to the unity of assumptions that bind even the most opposed ecclesiastical groups today is to recall “a standard plain, central Christianity (“mere” Christianity as Baxter called it) which puts such controversies of the moment in their proper perspective.”

One way in which controversies of the moment can be put in their proper perspective is to read not only modern books, but also old books. “If [a man] must read only the new or the old [books], I would advise him to read the old,” wrote Lewis. “It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.” The old book puts the new book in perspective, he says, because every age has its own unique outlook. Every age is “specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period.”

In this way, ‘going out of one’s own age’ leads to a realization of the characteristic assumptions that shape contemporary discourse. Once soaked in the teachings that have been held in common throughout Christian history, Lewis writes, you will have an amusing experience if you then venture to speak. “You will be thought a Papist when you are actually reproducing Bunyan, a Pantheist when you are quoting Aquinas and so forth. For you have now got on to the great level viaduct which crosses the ages and which looks

so high from the valleys, so low from the mountains, so narrow compared with the swamps, and so broad compared with the sheep-tracks.” Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical disputants need a greater acquaintance with Hooker, Herbert, Traherne, Baxter, Taylor and Bunyan, Boethius, St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and Dante to afford greater knowledge of the kinds of arguments which allow one to uphold supernatural religion and the teaching of salvation (always of primary importance to Lewis), against liberal modernity.

From the ‘deep’ perspective, even the divisions of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation could be seen in a different light. Despite their deadly disagreement about the

merits of a vernacular Bible, William Tyndale and Thomas More were men of a particular age. In retrospect, Lewis wrote, William Tyndale and Thomas More had more in common than they realized and “though they were deeply divided in temper as well as by doctrine, it is important to realize at the outset that they also had a great deal in common.” “They must not,” Lewis says, “except in theology, be contrasted as representatives respectively of an old and a new order.” Both were Grecians, as he puts it, advocates of the new scholarship, and both were “arrogantly, perhaps ignorantly, contemptuous of the Middle Ages.” Yet their age, which held to divisions that looked irreconcilable to them, in retrospect appear less than church dividing. How can, one might ask, such differences appear church dividing in light of the challenge presented to the common historical faith by the liberal theology of a Harvey Cox in Secular City?

But the object here is not to resolve the problems raised by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, but to note what Lewis has said about contemporary divisions within Anglicanism. It is obviously wrong to suggest that Lewis belittled real theological dispute. Lewis would not suggest that Thomas More, William Tyndale, John Fisher, and Richard Hooker or the Tractarians and Evangelicals of the 19th century are unworthy of reading. Rather, his point is that they ought to be read so to better understand ourselves and our age. This is touched upon by Roger Beckwith when he urges Anglo-Catholic priests to appreciate the Reformation Formularies, the 39 Articles and the Book of Common Prayer, just as Evangelicals should drink deeply of the teaching and theology of Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Patristic and Medieval metaphorical and allegorical Scriptural commentaries.

In his Letters to Malcolm, Lewis remarked that the key to Christian unity is not to substitute religion for God. He defended the 1662 Prayer Book against the liturgical reformers who had contracted the ‘liturgical fidget,’ yet at the same time he said that matters of liturgy or ceremony are not of central importance. Rather, changes are bad because disruptive to the person praying, and prayer is what matters. “A good shoe is the shoe you don’t notice. . . . The perfect church services would be one we were almost unaware of. . . . But every novelty prevents this.” Words should be the means to facilitate a knowledge of God. “For me”, he wrote, “words are in any case secondary.” If liturgical changes keep the stream of prayer from flowing, they are a stumblingblock for the prayerful. What is primary is nothing but God Himself.

As Roger Beckwith has noted, if Evangelical and Anglo-Catholic both willingly defend what Lewis calls supernatural religion and the message of salvation found in the church catholic, they have no reason to take issue with the historic prayer books. The eight points of disagreement noted by Beckwith are easily resolved from the standpoint of the common theological inheritance of western and English-speaking Christendom. Anglo-Catholics need to recognize the

importance of Beckwith’s first point—the ‘catholicity’ of the Protestant reformation, as church bishop Christopher Wordsworth declared, just as Evangelicals must accept that the Church of England did not come into existence in the sixteenth century. This would be a lesson for Anglicans as to the true and proper teaching of the Reformation, which established in the Church of England both the primacy of Scripture and the central historical teachings of the

Church, in a way that avoids the errors of our age.

Posted in Anglicanism, BCP, Churchmanship | Tagged Anglicanism, Anglo-Catholic, C.S. Lewis, Churchmanship, Counter-Reformation, Evangelical, Reformation, Roberta Bayer | 1 Comment »

Mr. John Wesley

Though the American Prayer Book has granted various civil offices different emphases in its state prayers, it’s been asked if a hasty substitution of the Presidency for Monarch might upset older notions of an Ordered Society? The potential problems invoked by such swapping has been discussed in several places, especially with respect to the Litany(1). Nonetheless, students of American church history are probably mostly familiar with John Wesley’s Sunday Service. Further discussion on the development of American state prayers allots Wesley a candidate for influence upon the United States BCP. While not comprehensive regarding the question, this post aims to open some discussion. Continue Reading »

Posted in Anglicanism | Leave a Comment »